People have been setting New Year’s resolutions for hundreds of years…and failing to make them stick for just as long.

How can you create effective New Year’s resolutions that you not only can keep, but which help you achieve your goals?

Today I’m going to talk to you about what a resolution is, different types of New Year’s resolutions and how to formulate interlocking resolutions to increase your success in the New Year.

What is a Resolution?

At its core, a resolution is a statement of commitment. It is a vow one makes to oneself to change one’s life in a specific way.

A resolution can also be a marker, a way to demarcate one’s past from one’s future. People often set resolutions in an attempt to draw a line in the sand between how they lived their life previously and how they would like to live their life in the future.

New Year’s resolutions are simply those resolutions set around the turning of the year. The dawn of a new year provides a useful time marker which can be used to draw a line between the past and the future. The end of the year can then be used to evaluate how one’s resolutions turned out.

Types of Resolutions

One can formulate a resolution in different ways—and how you formulate your resolution can affect strongly whether you successfully keep it.

The 3 main types of resolutions are:

- Goal Resolutions

A goal resolution states the end you want to achieve. Goal resolutions can be general, like “Lose weight”, or specific, like “Lose 10 pounds”. Goal resolutions describe the destination you want to reach, but not how to get there. - Process Resolutions

A process resolution states what actions you will take. As with goal resolutions, they can be general, like “Exercise daily” or specific, like “Do a 30-minute run daily”. Process resolutions describe the way you will move toward a goal rather than the goal itself. - Rule Resolutions

A rule resolution states a rule you commit to following. Rule resolutions provide clarity when willpower lags by pre-deciding what to do in specific situations. For example, “Always eat a salad first when eating out” or “No Facebook before 5pm”. Rule resolutions describe how you will chose which path to take while moving toward your goal.

Out of these three types of resolutions, process and rule resolutions work the best. Goal resolutions—at least those without any implementation intention—merely indicate what you want to achieve, but don’t provide a roadmap for achieving it. All resolutions work better when they are specific and measurable than when they are vague and general.

As you might imagine, you can combine these approaches in a single resolution. For example: “Lose 10 pounds by doing a 30-minute run daily and always eating a salad first when eating out.”

Using Interlocking Resolutions

Long resolutions, while more comprehensive, can be harder to implement. Instead, consider creating interlocking resolutions that can be remembered individually, but which support each other:

- Lose 10 pounds

- Run daily for 30 minutes

- Always eat a salad first when eating out

Creating multiple short resolutions makes them easier to remember, which makes it more likely you will follow them.

Of course, if you have 3-5 goals and then another 1-2 process and rule resolutions to support those goals, you can quickly have too long of a list of resolutions to remember. Which brings us to…

Make 2 Resolution Lists

As is often the case when you feel overwhelmed by too many items, grouping items into categories can help. The same applies for resolutions.

For resolutions, consider defining two lists:

- Motivation

What you want to achieve and why. Notice I added the “why” in here. While it technically isn’t part of the resolution, writing this down helps to remind you of the reason why you’ve adopted the resolution. For example: “Lose 10 pounds to reduce my cholesterol and improve my heart health”. - Implementation

How you plan to execute your resolution: the processes you will adopt and the rules you will abide by. This describes the path to success.

Put the implementation list somewhere you see it regularly, to remind you of the specific actions you need to take to achieve your goals. Use the motivation list as a reminder from time to time of why you created your implementation resolutions.

Alternatively, put the motivation list in a place where you’ll see it early in the morning, to gently remind you of what you’re aiming for and why. Then put the implementation list in a place where you’ll see it when you’re ready to take action, e.g., on the refrigerator, on your work desk, etc.

Instead of lists, you may find it useful to simply put resolutions on a sticky note and put them in the environments where you need them the most.

For example, “Lose weight to fit better into my existing clothes” might get stuck on the bathroom mirror while “No eating after 8p” might get stuck on the refrigerator door.

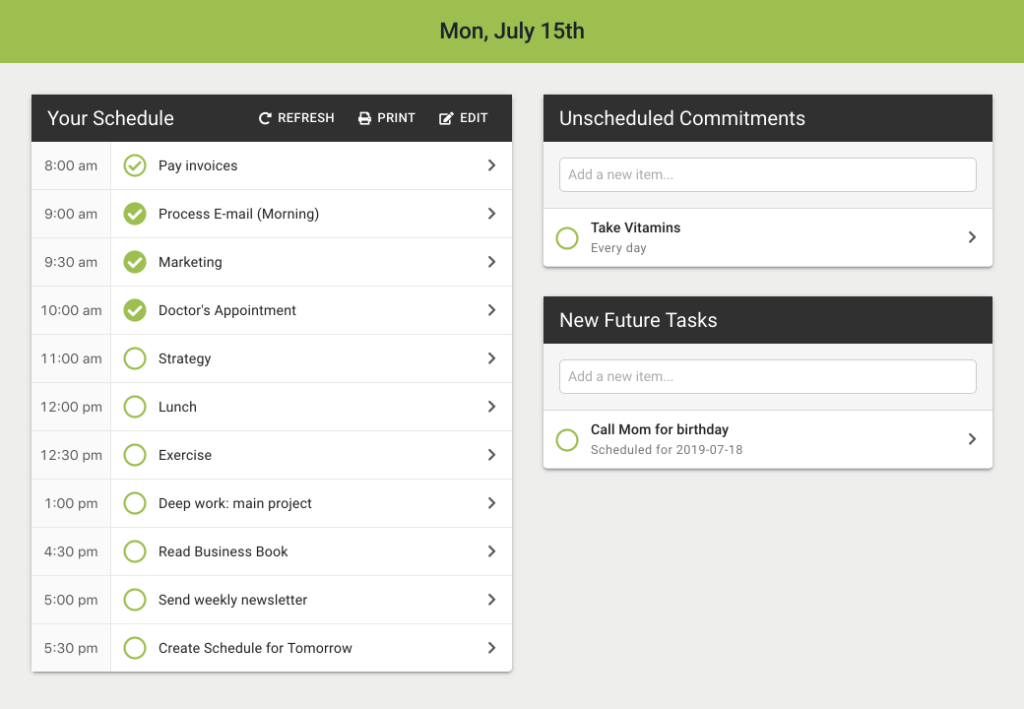

Define Metrics

Successful resolutions tend to be measurable. Without some metric to measure how well you’re keeping the resolution, it’s easy to trick yourself that you’re keeping it when you’re not, or to forget about what progress you actually did make toward the resolution, even if you didn’t achieve it.

Metrics can be defined in a few different ways:

- Distance

How close or far away are you from achieving your resolution? Distance metrics work best for goal resolutions. For example, “Lose 10 pounds”, “Read 12 books” or “Run 100 miles this year” all define distance metrics. Distance metrics help you visualize the progress toward your goal and can be tracked as a simple percentage toward your final number. - Frequency

How often are you acting on your resolutions? Frequency metrics work well for both process and rule resolutions. For example, “Stretch daily”, “Read 1 book a month”, or “No work on Sundays” all define frequency metrics. Frequency metrics ensure you implement your resolution consistently and can be tracked in a calendar or by an app like everyday.app. - Intensity

How much effort do your resolutions require? Intensity resolutions work well as an added layer for process resolutions. For example, “Stretch for 10 minutes daily”, “Read 5 pages each morning” or “Close open tabs every week for 1 hour” all define intensity metrics. Intensity metrics define a minimum level of effort, so it’s clear when you have kept to your resolution. They are best combined with frequency metrics.

Metrics help you understand how well you’re keeping to your resolutions. They act like the dashboard in your car, telling you how fast you’re traveling and far you’ve come.

Define Milestones

With metrics defined, you can define milestones to act as checkpoints on your progress throughout your year.

Monthly or quarterly milestones can provide an early warning that you’re getting off track, so you can take steps to adjust your approach to ensure you meet your resolution.

When creating milestones using metrics, it can be tempting to divide things evenly throughout the year. For instance, if my goal is to run 100 miles this year, I might create 4 quarterly miletones:

- March 31: Have run 25 miles

- June 30: Have run 50 miles

- September 30: Have run 75 miles

- December 31: Have run 100 miles

The problem with this approach is that life rarely runs smoothly, and small hiccups can snowball into larger misses. If you miss your March 31st goal by 5 miles, not only do you lose a bit of motivation, but now have to work even harder for your June 30th goal with that lower motivation.

Instead, consider front-loading your milestones:

- March 31: Have run 30 miles

- June 30: Have run 60 miles

- September 30: Have run 90 miles

- December 31: Have run 100 miles

Notice that the absolute number of miles for the first 3 quarters only increased by 5 miles (30 miles instead of 25), by now my New Year’s resolution will be 90% complete by the end of Q3. This gives me a buffer, in case things don’t go to plan, to still reach my goal of 100 miles by December 31st.

Design for Resilience

When setting New Year’s resolutions, don’t assume you’ll have the same amount of energy and motivation throughout the year that you have on January 1st. Instead, design your resolutions to account for ups and down.

First, consider setting your milestones based on how you anticipate how your energy and motivation might change throughout the year. Keep in mind that success breeds motivation. So, if you can design your resolutions to have early successes, it’ll be easier to build the momentum to carry them through the entire year.

Second, consider using the stoplight method (also known as the staircase method) for defining resolutions. Define two levels of effort for each resolution:

- Green: The ideal level of effort you want to put toward the resolution. For example, “Run 30 minutes daily”.

- Yellow: The minimum level of effort required for you to feel like you’re keeping the spirit of your resolution. For example, “Walk 10 minutes daily”.

On days when your motivation is normal, aim for your green level. On days when your motivation or energy is lagging, force yourself to at least do your yellow level. If you fail that, you’ve hit the red level and lose momentum. When that happens, take a break to regain your energy and pick a date to restart your resolution and build back up your momentum.

Finally, avoid thinking of your resolutions as all-or-nothing. When you do that, any small perturbance causes you to abandon all efforts. Instead, think of your resolutions as “getting better”, where even if you can’t achieve a perfect record of keeping your resolution, you can do better than you would have done without the resolution.

In Conclusion

Resolutions can be made more effective by defining interlocking resolutions that combine both motivations and implementations.

By defining your resolutions using metrics, you can see your progress throughout the year, so you can adapt when you get off track.

And by designing for resilience upfront, you can help ensure that obstacles and your changing energy and motivation throughout the year don’t derail you.

Before you go, one more thing: Read Anti-Resolutions: What WON’T You Do This Year? for another perspective on resolutions.