Effectively executing a plan requires more than simply putting in hours. If you want to be working smarter, not harder, you need to be doing four things while executing your plan:

- Work

Spend time to make progress on your commitments. - Recharge

Take time to relax and refuel. - Assess

Evaluate how your plan is going. - Patch

Revise your plan based on your assessment.

Often we stay too long in the work phase and forget about the others until our productivity has started to suffer or we’ve drifted too far off course. Ensuring we renew, assess and revise at regular intervals—before we feel we need to—is critical to effective execution.

Work

At their core, all productivity strategies and methodologies boil down to helping you become better at doing work—though each may have their own definition of what “better” means.

For Day Optimizer, “better” means:

- Aligned

Your work reflects your goals, desires and values. - Sustainable

You work at a pace that isn’t unrealistic or overwhelming. - Impactful

You work mostly on work that is important to you and others. - Mindful

You maintain an awareness as you work, both to savor it and to avoid getting lost in work and veering too far off course.

The process thus far was designed to help you create a plan that reflects this better way of working. But what about doing the work itself? Can we improve how we work our plan?

Getting Started

Getting started can often be the hardest part of working. Once we get started, momentum kicks in to help us power through. Or we get into a flow state and time simply melts away.

Even if we know we can reach momentum and flow, getting there is not always easy. What can help us get started when we’re struggling?

Jumpstarts

A jumpstart is a technique that shifts your mood into a specific state to help you get started.

Jumpstarts are personal. Some will work for you; others will not. Experiment to find the ones that work for you and then use them whenever you are struggling to get started.

Jumpstarts also depend on what state you want to shift into. Different types of tasks may require different jumpstarts.

Some jumpstarts to experiment with include:

- Edit to Create

To get into the mode to create, try editing first. Editing shifts you into an active role with your creative medium, which prepares you to tackle a blank slate. If writing, edit one of your old articles—or even someone else’s. If coding, refactor your code. If painting, touch up a prior piece. - Create to Flow

When you have nothing to edit, start the creation process with a purposeful throwaway. The aim is merely to get your creative juices flowing. Write about what you see in front of you, improvise a song about your troubles writing a song, write a sarcastic opening to your report or proposal. Add constraints to aid the creation process: pick an unusual theme, decide that you cannot pause during the process, do it standing up, etc. - Play to Warmup

Play a game that requires you to use the same physical or mental muscles you need for your main task. Identify games you can play quickly that you can quickly disengage from, so you use them as a jumpstart, not a distraction. - Frivolous to Important

Start with a small, low-priority task that’s easy to do. Accomplishing the task will give you momentum to tackle your more important tasks. To lift your mood at the same time, choose an indulgent task—one that you really want to see done, but have been ignoring because it’s low priority. - Dress the Part

Change your clothes or appearance to shift your mindset. Ideally do this 10–15 minutes before your anticipated start. Put on your running clothes to nudge yourself to run. Dress up in a suit before doing sales calls. Associate tokens like hats, silly socks or other articles of clothing with specific states to get brought quickly back to those states when you put them on. - Shift Your Environment

Switch to a different room or switch something up in your environment to cue your brain that you will be doing different work. This is the environment equivalent of Dress the Part.

Pay attention as you go throughout your day to what small activities give you energy or shift you into a new mindset. Write these down and give them names so you can easily reference them. Then next time you’re having a hard time getting started, try out one of your jumpstarts to help you shift into the task you’re having trouble with.

Key to successfully using jumpstarts is to avoid getting lost in them. Set yourself a time limit, and monitor how long it takes for you to move from your jumpstart to your main activity. You may discover certain activities act as procrastination devices, not jumpstarts. Avoid those in the future.

The Difference Between Mood and Energy

A key to using jumpstarts effectively is recognizing the difference between not being in the mood and not having the energy to get started.

If you find yourself procrastinating on a task by diving into another activity with full energy—such as surfing social media or cleaning—then your problem is not energy, but mood. In this case, use a jumpstart to shift your mood.

However, sometimes no matter how much we want to work, we don’t have the energy. We’ve pushed ourselves too far or didn’t get enough sleep the night before and are trying to slough it through.

In these cases, a jumpstart won’t work. You need something else.

Accountability

Accountability is an obligation we feel toward ourselves or others. It comes in varying forms, pushing us to do what we said we would do even when we don’t feel like it.

What are some types of accountability we can use to get started?

Commitments

Commitments are a type of ”implementation intention“, an if/then plan that nudges us toward doing what we said we wanted to do. They are a form of self-accountability.

By “committing” to a to-do for a specific day or week, and then ideally scheduling it at a specific time, we plant a seed in our brains that helps us fulfill our intention.

Scheduling a commitment at a specific time slot creates an objective criterion that helps us beat procrastination. If you said you were going to start something at 10am and it’s 10am, it’s harder to justify why you shouldn’t get started.

Accountability Buddies

One-on-one accountability works well for many people.

When you agree with another to hold each other accountable, it’s called having an accountability buddy. This setup shifts the obligation from a personal obligation to a social one.

Knowing someone else will be disappointed in you can provide strong motivation to push through any blockages to get started.

Accountability buddies don’t work for everyone. Some people are less sensitive to social obligations; though even in these situations, accountability buddies can serve as a mirror to help you more clearly see how well you are holding to your own personal commitments.

Body Doubles

For those on the opposite end of the spectrum, who are extra sensitive to social obligations, merely working in the presence of another can help them stay focused and get to work.

For some, working along side someone else, even if they are not actually working together, can provide the social pressure needed to limit procrastination and get started.

Be careful though. Working with others can also be distracting if they are prone to interrupt you too often or use you as a source of distraction.

Pacing Yourself

Once you get started, what does your work look like? Do you work continuously in a single block? Or do you work in shorter sprints followed by brief breaks?

Pacing refers to the strategies you use to break up your work block to manage your energy and effectiveness.

Sprints

The Pomodoro® Core Process is a famous pacing technique where you work in sprints of 25 minutes each followed by a 5 minute break. At the end, you make a checkmark on a piece of paper or in an app, then do another sprint. After 4 sprints, you take a longer break.

Whether you use a 25 minute sprint length or longer, working a specific cadence of work and rest cycles can be powerful. The key is to take a rest before you feel like you need it. By the time you recognize you need a break, your productivity has already suffered.

If you choose this approach, aim to make your sprints no longer than 90-120 minutes. Research[6] shows that working longer sprints than this hurts our productivity.

Single Blocks

The opposite of working in sprint is to work on a single commitment for a single block of time. When creating a schedule, this is often the default way we think about working.

The same recommendation applies when scheduling out single blocks of time: aim to work no longer than 90-120 minutes before taking a break or switching to a different task. Longer than that and our concentration and performance starts to suffer.

Scheduling blocks of time and working in sprints can be combined. If you use a 25 minute sprint length followed by a 5 minute break, then you can use that to break up a 90 minute or 120 minute commitment.

Pacers

Do you ever find yourself getting lost in work and spending more time than you intended doing a task or activity?

Pacing timers, more simply called “pacers”, can help. Pacers bring an awareness of time passing into your work. They help you keep track of the speed at which you are working, to motivate you to work at a faster pace—or at least at your desired pace.

For example, to become aware of time passing while working, set a timer to go off every 15 minutes.

This divides a longer task into shorter intervals and briefly brings your awareness back to how time is passing each time the timer goes off. This awareness can then be used as motivation to work faster, to be less of a perfectionist, or to be more realistic with what you can accomplish.

Pacers aren’t for everyone though.

The stress of a clock ticking down or a timer going off repeatedly can cause procrastination, distraction and mental blocks.

Use pacers if you find yourself being too much of a perfectionist, going down rabbit holes, or working at a slower pace than you’d like.

If you choose to experiment with timers as pacers, use a gentle tone that increases volume gradually. If using your phone timer, search for tones like chimes, bird calls or ocean waves in your tone store.

Checkpoints

Regardless of whether you use single blocks of time or sprints, checkpoints can be a useful technique to help you make adjustments while working on a commitment.

A checkpoint is a minute or two during which you step back from your work to evaluate where you are based on what you want to get accomplished during your current work block.

Checkpoints serve as a tool to realign and rescope your work, to help you better achieve your goal.

Most time management is scope management.

When working on a task or project that is taking longer than we originally estimated, we can choose to work longer to complete the original vision, or we can change the vision to reduce the time required.

While at the beginning, we often aim to simply work longer, at some point we shift into reducing the scope to be able to finish the task or project in a reasonable amount of time.

Checkpoints help us take control of this process earlier. Instead of waiting until the end of our allocated time to figure out where we are within our task or project, we can decide to stop while working to do that evaluation, and then make adjustments earlier.

For instance, if you are working a 90 minute block, you might decide to do a checkpoint after 30 minutes, again after an hour and then one last time 15 minutes before the end.

Scheduling your checkpoints ahead of time is ideal, since it’s easy to get lost in work and forget to take a step back. But even ad-hoc checkpoints provide value.

If you are using pacer timers, these become logical points to have a quick checkpoint.

Structuring Your Work Time

If pacing yourself helps you manage your energy and effectiveness during a work block, structuring your work block helps guide what type of work you are doing during that block.

The Prep > Do > Wrap Framework

Every work block has three potential phases:

- Prep

Set up your environment, set an intention for the time block and “load” your mental state. - Do

Do the work itself. - Wrap

Set yourself up for success next time by “saving” your mental state and restore your environment back to a neutral state.

When we don’t take the time to properly prepare for our work, or rush immediately to the next commitment and don’t take time to wrap up, our productivity suffers.

Being explicit with our prep and wrap time can help fix that.

Whenever you start working on a commitment, set aside the first 5-10 minutes as prep time and the last 5-10 minutes as wrap time.

This is particularly important for the wrap time. While it can be hard to ignore prep work, since we often must do it before diving into work, it’s easy to work straight up to our cut-off time and not spend any time wrapping up.

For tasks that require more than a single session to complete, taking notes and writing down next steps make it easier to get started next time.

Meanwhile, resetting your workspace by filing papers, closing browser tabs and clearing off your desk makes it easier to focus on your next commitment.

Time Block Blueprints

For time blocks you do regularly, such as writing an article or producing a report, it can be helpful to define a blueprint.

A blueprint consists of the steps you need to execute and the rough durations of those steps during that time block.

For instance, say you want to spend 90 minutes writing a blog post once a week. Leaving your time unstructured, you might find that you’re often running over.

Instead, you create the following blueprint:

- First 30 minutes

- Outline: 5 minutes

- Write post: 25 minutes

- Second 30 minutes

- Take a break: 5 minutes

- Read with fresh eyes: 5 minutes

- Finish draft: 20 minutes

- Final 30 minutes

- Break: 5 minutes

- Read with fresh eyes: 5 minutes

- Edit to create final version: 10 minutes

- Find photo: 5 minutes

- Publish: 5 minutes

A blueprint isn’t a structure you need to follow exactly, rather a rough guide that shows you how to work effectively within a time block.

By structuring your time within a time block, you can more easily see where you are relative to where you should be and make adjustments, such as reducing scope or changing your approach to the work.

Recharge

Constant work with no breaks reduces our productivity. Our brains and bodies get tired and stop working at maximum effectiveness. The result is lower energy, reduced creativity and poorer decisions.

When this happens, we need a break to recharge.

Breaks can help you:

- Clear your head

- Release tension and stress

- Rebuild energy

- Stretch and activate your body

- Reset attention and motivation

- Improve memory formation

But what type of breaks should you take and how often should you take them?

Types of Breaks

Breaks have many different aspects to them:

- Does the break involve stillness or movement?

- Does the break target the body, the mind or both?

- In what environment does the break occur?

- What else is being done during the break, if anything?

The Day Optimizer methodology group breaks into categories:

- Rest

Focused on stopping directed thought or activity. Examples include taking a nap, meditating or day dreaming. - Movement

Focused on moving the body. Research[7] shows movement breaks enhance creativity more than sitting breaks. Examples include stretching, taking a walk or even standing up for a minute or two. - Breath

Focused on shifting the state of your body through breathwork. Examples include deep breathing for relaxation or the 5-3-3 breathing technique for an energy boost. - Refuel

Focused on eating or drinking energizing food. Examples include eating a meal/snack, or drinking tea/coffee. - Autopilot

Focused on a mindless activity that allows the mind to rest and wander. Examples include emptying the dishwasher, cleaning and other chores. - Ritual

Focused on processes imbued with special meaning that help us release stress or negative thoughts. Examples include taking a shower, savoring a cup of tea, or other mindfulness rituals.

Beyond these categories, consider the environment within which the break is occurring.

Do you remain in your work environment or move to another environment? Do you take the break in nature or in a streetscape?

Experiment with different types of breaks in different environments to learn what works best for you, and in what situations to use each.

When to Take a Break

Knowing that you should be taking breaks is not the same as taking them. Research shows that we often wait too long to take a break. By the time we recognize we need to take a break, our performance has already been suffering.

Thus, the best strategy is to schedule breaks regularly. Throughout the day, plan to take a break at least every 60-90 minutes. Throughout the week, plan to take a break every 4-5 days. Throughout the year, plan to take a break every few months.

Longer breaks provide greater resets than shorter breaks, so think about what break strategy will help you the most.

For instance, the Pomodoro Technique® recommends a 5-minute break after every 25-minute sprint and then a longer 15-minute break after 4 sprints (about every 2 hours of work).

Many office workers take shorter morning and afternoon coffee or tea breaks combined with a longer lunch break.

Whatever strategy you choose, it helps to schedule your breaks. When we schedule breaks, we give ourselves permission to take them and ensures we take our break before our performance starts suffering too much.

It’s worth repeating: if you feel like you need a break, it means that your productivity has already been suffering.

Breaks to Overcome Roadblocks

Scheduled breaks help us recover from the general fatigue produced while working. But sometimes we encounter an obstacle that feels impossible to overcome.

It feels like we’re banging our head against the wall or trudging through sludge. No matter how focused or determined we are, we can’t push through it.

When this happens, it’s time to step away and take a break.

Whether it’s writer’s block, a perplexing problem or a difficult situation, it’s hard for us to see potential solutions when our focus is narrowly targeted at the problem we think we see.

Taking a break allows your mind to roam and your body to recharge so you can return to your roadblock with fresh eyes. Many eureka moments of famous inventors and creators came not while deeply focused on work, but while out for a walk, taking a shower or silently meditating.

Use breaks not only as a tool to restore your productivity, but to enhance your creativity when you find yourself stuck.

Assess

Plans rarely play out exactly how we envisioned them. That’s why it’s important to periodically take a step back and evaluate how things are going relative to your plan.

By assessing what you have accomplished, what you still need to do, and what the rest of your available time looks like, you can take steps to reorient early before you get too far off course.

Review Your Accomplishments

First, look at what you have accomplished so far. Often we under or over estimate what we have accomplished.

Reviewing your accomplishments grounds you in reality. If you’ve already done a lot, it can ignite a feeling of productivity that can boost your motivation to do more. If you haven’t done much, it can be a call to action to rally your energy and focus on your priorities.

Aside from the quantity though, reviewing your accomplishments help you evaluate the quality of your work.

Have you been focused and working at your maximum effectiveness, or have you been trudging through your work putting in the minimum required effort?

Take into account how you’ve been working thus far as you assess the rest of your day so you can make better adjustments to your plan.

Estimate Your Remaining Effort

Now that you know what you’ve done and how well you did it, look at the rest of your plan and estimate how much effort remains.

If you allocated time to each commitment, add up the durations of all the commitments you haven’t yet worked on. This is your total remaining effort.

If you are suffering from lower productivity than normal, adjust this remaining effort to account for this by either multiplying the total by a fudge factor like 1.5 or 2, or increasing the allocation for specific commitments you know will take you longer.

Project Your Available Time

Once you know the total amount of effort you have remaining, calculate the amount of time you have left in your day.

By comparing your remaining effort against your available time, you can see whether you are on track with your plan, and if you are behind, can make adjustments to focus on your priorities.

With your assessment done, you can start patching your plan to better match reality and ensure you put your effort toward the items that will have the greatest impact on your goals and desires.

Patch

To paraphrase Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke:

No plan survives contact with reality.

The perfect vision your plan lays out seldom comes to pass. The unforeseeable and unforeseen conspire with interruptions, distractions and procrastination to play havoc with your plan.

On good days, you’ll accomplish most or all of what you intended to, in roughly the order you planned it.

On bad days, if you accomplish just one of your priorities at any point in your day, you can consider it a success.

One method to turn a bad day into a good day—or at least a better one—is to assess and reorient as you go through your day.

Take the time to patch your plan to make it better reflect the reality of the day you are experiencing rather than the day you imagined.

Ways to Reorient Your Day

How you approach patching your day depends on how your day is going relative to your plan.

If you are only slightly behind or slightly ahead, minor modifications will suffice—if you need to make modifications at all. In this case, keep your existing plan and simply swap or reorder items as necessary.

If you are far behind or far ahead, consider scrapping your current plan and starting from scratch. Take everything you haven’t worked on yet today, start from the Allocate step of the CASE planning process and create a new plan for the rest of your day.

When modifying your existing plan, follow these steps:

- Prioritize anchors

What are the things that must get done today?

Move these to the time slots where you’ll have the highest energy and focus. - Remove bumpers

What are the things that can be skipped or are no longer relevant?

Mark these as Skip Today or Won’t Do so you know to ignore them and to free up the time allocated to them. - Fill in core commitments

What remaining commitments should get done, but are lower priority than your anchors?

If you have enough available time after prioritizing your anchors, or decide you are willing to work late, keep these on your plan. Otherwise, mark them Skip Today to ignore them and make sure you end your day at a reasonable time.

After making adjustments, review your new plan to make sure the timing and order makes sense for your energy for the rest of the day.

Handling New Commitments

When a new appointment or task arises after you create your plan, how do you handle it?

Don’t immediately add it into your plan.

If it requires urgent attention, put aside your plan and address it immediately.

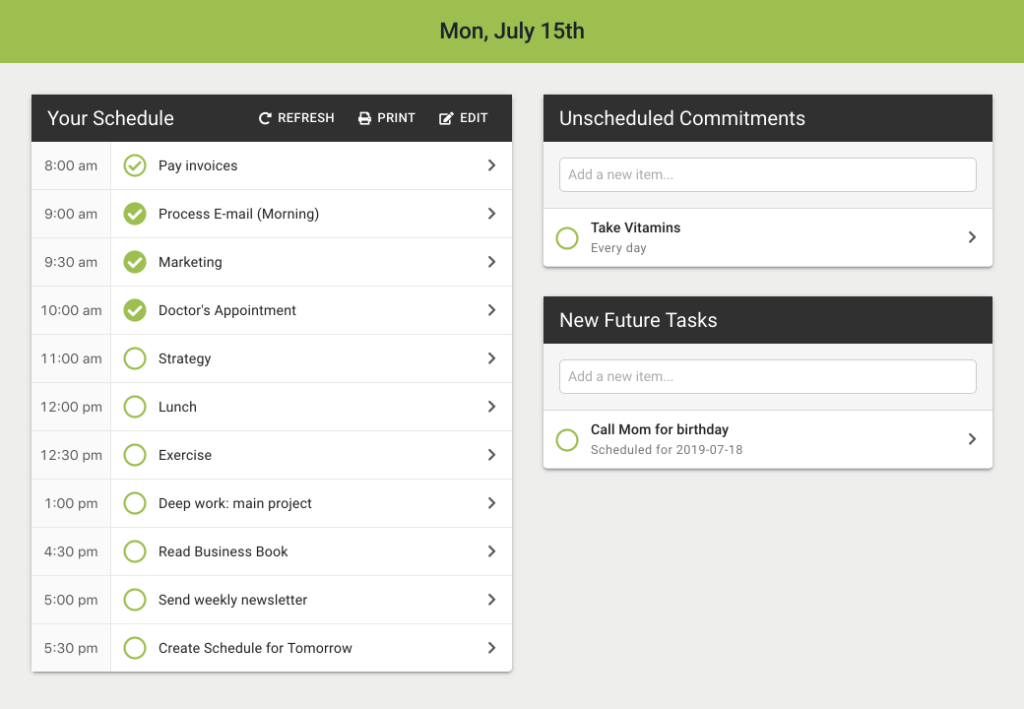

If it isn’t urgent enough to stop what you are doing immediately, add it into a staging area as an “unscheduled” or “unallocated” commitment. Don’t interrupt your current work to update your plan. Instead, schedule a time to assess and patch your plan and review the new commitment at that point.

When it comes time to review the commitment, avoid the tendency to assume that because it’s new that it’s the priority. Evaluate it against your current commitments by doing the following:

- Allocate Time

Decide how long you want to spend on the commitment today, so you have an idea of how much time you must free up to work on it. - Make Room or Defer

Go through your existing plan and ask yourself what can be removed to make room for this new commitment. If the answer is nothing, then defer the commitment to the next day.

When you have multiple new commitments to be processed, allocate time for all of them first to ensure you don’t under allocate once you see what your actual time limitations are.

Marking Items Skip Today or Won’t Do

When using software that supports Skip Today and Won’t Do, you can simply mark an item off using one of these statuses. But how do you handle this when working on paper?

If you like to cross items off, use a wavy line instead of a straight line to indicate Skip Today. To mark an item as Won’t Do, cross it off with a wavy line, but then also underline it to emphasize you won’t ever do it.

If you prefer making a checkmark next to the items on your list, you can use an X to indicate Skip Today and an X with an underline underneath to indicate Won’t Do.

Switching Your Plan Type

While normally you want to use the same type of plan for the entire day, sometimes it makes sense to switch to a different type of plan.

If you started your day with a daily schedule, but are having too many interruptions, switching to a time bucket allows you to still prioritize your remaining commitments taking into consideration the time they require, without needing to schedule them into specific time slots.

Likewise, if one commitment absolutely needs to be done today and you know you won’t have time anything else significant, you might decide to switch to a commitment list with your anchor commitment at the top, and otherwise only key appointments or activities remaining on the list.