Multitasking doesn’t work. Numerous studies have shown that. So why am I writing an article about how to multitask effectively?

Two reasons:

- You’ll do it anyway.

- A framework can help you do it better.

So let’s bring some nuance to the discussion around multitasking…

Not All Multitasking Is the Same

Despite how the term is used, not all multitasking is the same—so why would one rule always apply?

When driving a car, we switch seamlessly between the gas pedal and the brake while steering and watching the road—three different activities that we multitask seamlessly because we’ve integrated them into our muscle memory.

When running a business, we seamlessly switch between different priorities throughout the day, often handling a dozen or more tasks per day.

And, yes, sometimes we’re in an important meeting, trying to listen while answering our emails at the same time.

These are not all the same.

5 Ways of Thinking About Multitasking

The classic definition of multitasking is “doing two or more tasks simultaneously”. But what type of tasks and how do we define “simultaneously”?

I propose (at least) 5 different ways to think about multitasking:

- Macro vs Micro

- Physical vs Mental

- High vs Low Mental Load

- High vs Low Context

- Quality vs Quantity

Each of these four ways of thinking point toward a different solution for effective multitasking.

Macro vs Micro Multitasking

Much advice against multitasking is focused on micro-multitasking; but macro-multitasking can be just as ineffective—or effective—depending on how you do it.

Micro-multitasking is when we attempt to switch rapidly between different tasks within short period of time. For instance, trying to process our email while listening to a webinar.

Studies have shown that people who can do true micro-multitasking are extremely rare; instead, most of us perform worse at both tasks when we multitask. And developing a habit of always micro-multitasking can lead to burnout by not allowing our mind to ever truly focus.

Conversely, macro-multitasking involves working on multiple tasks over a longer period of time.

When an employer is looking for someone who can multitask well, they are usually looking for someone good at macro-multitasking, not micro-multitasking. That is, can you handle more than one responsibility at a time.

Even if we focus exclusively on one task at a time, the switching costs from jumping between competing priorities throughout the day can be draining for the human brain. It can make us feel like we’re making less progress and that we have a never-ending list of things to do.

It can also make us less productive.

Prep and Wrap Time Slow You Down

Most tasks require some type of preparation before we can be fully productive doing the task. For physical tasks, this might involve getting out the equipment required and setting up our workspace. For mental tasks, this could involve switching into the mental state required for the task and loading any necessary information into your working memory.

Likewise, many tasks require some type of wrap-up where we put away our equipment or take notes to quickly get to the same mental state next time. We can skip wrap-up, but we’ll often need more prep time later to restart the task—so we take the productivity hit either way.

The more often you switch between tasks, the more time you are spending in the prep or wrap-up phase and the less time you are spending in the doing phase where you are most productive.

The same applies, of course, for micro-multitasking, except that the mental prep and wrap-up is done by your brain unconsciously, so it’s harder to notice the extra effort being spent.

Physical vs Mental Multitasking

Pat your head while you rub your tummy…now switch and rub your head while you pat your tummy. Many of us have played this game as children and know how difficult it can be.

Even as an adult it can be difficult to do it seamlessly—there’s often a second or two where you get momentarily confused before getting back into the rhythm of the task.

Now try something different: read the previous two paragraphs aloud, but every sentence, switch between patting your head and rubbing your tummy.

Did that feel easier?

Doing two physical tasks or two mental tasks simultaneously is harder than doing one physical task and one mental task. Why?

I suspect it’s because physical and mental tasks use different parts of the brain (I couldn’t find any research in my brief literature search on this, so this is based on my personal experience).

Use Different Parts of Your Brain

Your brain can clearly process more than one thing at once. Otherwise it would be impossible to breath, walk and talk on the phone all at the same time.

One of the core problems with attempting to multitask is attempting to use the same part of the brain on two different tasks. To do this, your brain needs to constantly switch between the two tasks—it can’t do them in parallel—and your productivity will suffer.

Or, to summarize:

Multitasking with the same part of the brain = bad

Multitasking with different parts of the brain = maybe okay?

Let’s dive into more nuance though.

High vs Low Mental Load

While mental vs physical can be a useful rubric for multitasking, mental load—the amount of cognitive effort a task requires and how that compares to the total amount of mental capacity you have in the moment—can be more useful.

The reason you can breath, walk and talk on the phone at the same time is because the mental load of these tasks differs dramatically.

Breathing is autonomous. You do it automatically whether you think about it or not. Walking is one level higher in mental effort: you need to consciously decide where to go, but (generally as an adult) you don’t need to exert conscious effort on how to walk.

By comparison, talking on the phone—especially if it’s a conversation that requires intense focus—can require a lot of mental effort.

Pay Attention to Your Mental Capacity & Load

Imagine your brain as an electricity generator and each task as a device that is consuming that electricity.

When you are well rested and able to generate a lot of electricity, you might be able to handle more than one task that requires that electricity. But when your mental energy capacity is low, or a task is demanding, any additional load will wreck your productivity.

Going back to our walking and talking on the phone example: if you’re walking to be on time for an appointment in a city you’ve never been before, talking on the phone at the same time may overload your circuits—the mental energy required to navigate an unknown city is high and you just don’t have enough leftover capacity to talk on the phone too. However, if you’re walking the track at your local park, where you have essentially zero metal load for your walking task, talking on the phone—multitasking—is easy.

Bottom line: Pay attention to both your mental capacity and the effort required by each task when deciding when to multitask.

Caveat: We often don’t recognize when our mental capacity is diminished or when we’re overloading our system. Err on the side of doing less and pay attention to your body and mental state.

High vs Low Context

Earlier I mentioned how some tasks require more preparation before you can reach full productivity. I like to call these high-context tasks.

High-context tasks are those that require loading your brain with background information before they can be effectively worked on.

For instance, if I stopped writing this article at this sentence and decided to resume writing at some point in the future, I would need to skim the article to remind myself what I had already written and gain the context for where I was in the flow of my writing.

Conversely, if I’m emptying the dishwasher, I can walk away, then come back later and resume exactly where I left off with little to no mental effort (other than draping the dish towel over the dish rack to remind me that the dishes are still clean).

Tasks with low context can be switched between with relative ease. The higher the context required, the longer it will take when switching between tasks before you reach full productivity, and the less you should attempt to multitask with these tasks.

Pay particular attention to this when macro-multitasking. There is a ton of advice recommending that you don’t micro-multitask, but far less advice telling you to avoid macro-multitasking.

Some complex tasks require so much context that you may need to set aside entire days or weeks just to focus on that task. Difficult programming problems often fall into this category for me.

Cal Newport’s Deep Work and Paul Graham’s Maker vs Manager Schedule both address the negative effects of macro-multitasking for high-context tasks.

Decaying Context

One thing to note about multitasking with high-context tasks:

Context has a decay rate.

What I mean by this is that context doesn’t simply disappear when you switch tasks.

Sure, if you jump to another mentally intensive task that requires all of your mental bandwidth to handle, you may push out all of the context from the previous task.

But if you switch to a low mental load task that uses other parts of your brain, you’ll often be able to switch back to the high-context task and maintain much of the context.

Likewise, the longer you are away from a high-context task, the more context you lose.

Often it is better to schedule several hours in a single afternoon to tackle a high-context task than to spread that task over time blocks spread across multiple days. Theme days and theme weeks can help you avoid this form of macro-multitasking with high-context tasks.

Quality vs Quantity

The final thing to talk about related to multitasking is what your quality target is. Multitasking will often degrade your performance—but how much does that matter?

While listening to an audiobook alone in a chair in a dimly lit room might allow us to focus fully on the words being spoken, sometimes getting every exact detail is not necessary. Sometimes we only need the gist—a lower quality rendition in our brains that captures the major points.

Likewise, not everything you produce needs to be 100% perfect.

Knowing when to aim for quality vs quantity is key to being successful in life. What multitasking does is allow us to achieve more, but with a lower quality.

Multitask Strategically

As long as you keep this in mind, you can use multitasking strategically.

When you need to produce high-quality output, put away all of your distractions, create a time block for deep work and avoid even the hint of multitasking.

When you don’t need the highest quality, but need to get more done, use the framework laid out in this post to decide when and how to multitask.

Finally, keep in mind that it’s a spectrum and you can switch between these as needed.

For instance, you could produce a bunch of low quality drafts in an environment where you have more distractions and interruptions, then later schedule time to single task and convert those drafts into high-quality polished pieces.

Summary

Unlike other productivity experts, I’m not going to tell you to never multitask. Multitasking has its place in our modern work life and is a valuable time management skill.

But knowing when and how to multitask is critical to multitasking effectively. Keep in mind these general rules as you decide when and how to multitask:

- Prefer macro-multitasking over micro-multitasking.

- Choose tasks that use different parts of the brain when multi-tasking (e.g. physical & mental).

- Monitor your mental capacity in the moment and keep your mental load well under that capacity.

- Avoid multitasking on high context tasks—even macro-multitasking for very high context tasks.

- Multitask strategically based on your quantity vs quantity goals.

In the end, it’s important to limit how much of your day you spend micro-multitasking, so you give your mind time to be focused and relax, and to manage how you macro-multitask so you maximize your productivity in relation to your available mental energy, the context level of the task and the quality you are aiming for.

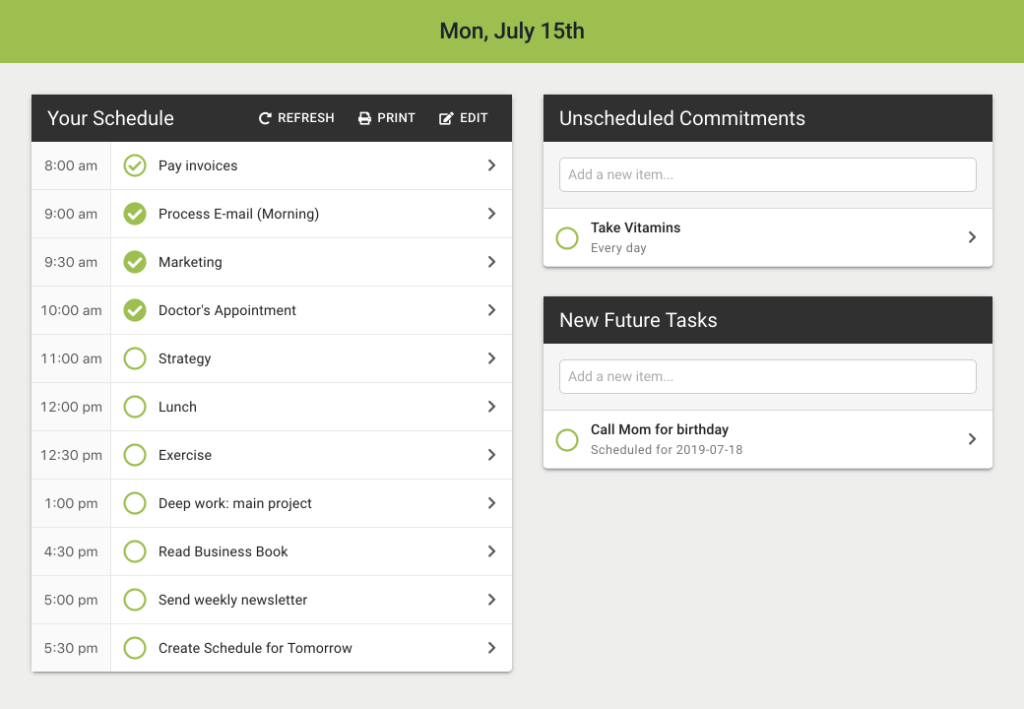

Need help scheduling your day to effectively macro-multitask?

Check out Day Optimizer, a digital day planner that uses guided workflows to help you build an effective daily schedule. Build a schedule using neuroscience principles that helps you create the right flow in your day to build and maintain your productivity. Register now for a free 7-day free trial.