Distractions are a part of life, but sometimes they can steal our attention spans and overwhelm us. If you have ever wondered, “Why do I get distracted so easily?”, you are not alone.

Distraction triggers are catalysts that divert our attention and focus, interrupting our current task. By identifying these triggers, we can develop strategies to manage or even eliminate them, enhancing our ability to maintain focused attention.

Let’s dive in to understand more about these triggers and how to deal with them over different periods of time.

Finding Your Triggers With a Distraction Log

The first step towards managing distractions is understanding their origin. When we get distracted, it always happens for a reason. Some trigger, be it sleep deprivation or lack of clarity about a looming task, causes the distraction.

If you can learn to identify your common triggers, you can develop strategies to mitigate or eliminate them, helping to improve your focus and tackle your list of tasks.

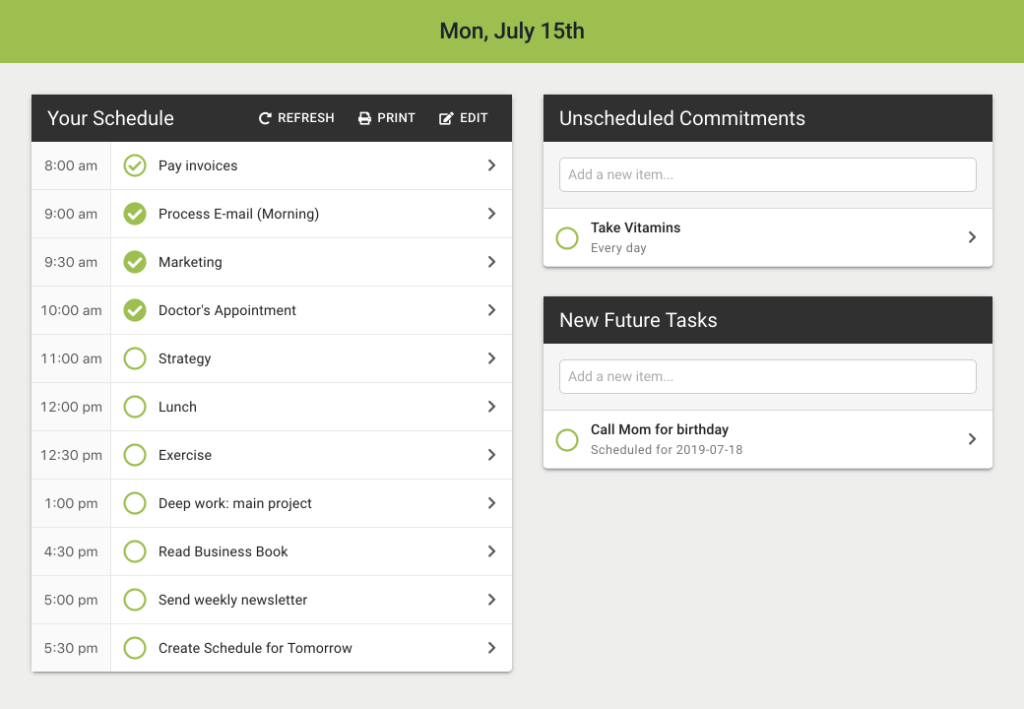

One method of doing this is to create a trigger log: a log of every time you got distracted and why. It could be external stimuli or internal issues like panic attacks or low cognitive performance in the late afternoon.

Create a spreadsheet with the following columns:

- Day of Week

What day of the week was it? Fridays have a different distraction profile than Mondays or Wednesdays. - Time

What was the time of day? As our energy and focus shift throughout the day, so does our distractibility. Are you a morning person or an evening person? This affects your peak performance time. - State

How were you feeling? Elevated stress levels? Nervous? What was your environment like? Hot? Humid? Noisy? Writing these things down can help you become aware of non-obvious triggers. - Primary Task

What were you working on when you got distracted? Was it one of your urgent tasks or a less demanding single task? - Trigger

What caused you to be distracted, as far as you can tell? Was it due to tiredness, lack of clarity or some internal stimuli? - Distraction

What did you do to be distracted? What activity or state did you switch into? Was it a digital distraction or emotional procrastination? - Length

How long were you distracted for? Documenting this can help manage your mental energy better. - Resolution

Did you get back to your primary task, and if so, how? - Notes

Was there anything else you want to remember for when you look at this log later?

Once you start paying attention to your triggers, you’ll start noticing your distractions sooner, and get more skilled at identifying their causes. This practice will make your daily plans more effective.

Internal vs External Distractions

Triggers can be internal or external.

Outside triggers like digital distractions are the easiest to understand. If you get a notification on your phone, that’s an obvious distraction trigger.

Internal triggers are trickier. Were you feeling hungry? Was your bladder getting full? Did anxiety about a task build to the point where it took over? Stress responses can also lead to Emotional Procrastination.

Learning how to identify internal triggers involves connecting with our body and mind more—becoming more aware of what our mental and physical states are—so we can address them before they control us.

Diffusing these triggers can be as simple as taking a five-minute break or pausing a moment to let the feeling drain out of our body and pass.

Breaking Free of Distractions

Once you have spent time logging your distractions, scan through your log and see if you can identify any common themes.

Are there certain triggers that occur frequently? What strategies can you employ to avoid these triggers, or, if they cannot be avoided, avoid getting distracted when these triggers occur?

Written rules can be useful to help minimize the decisions you need to make when these triggers occur, and make it easier to implement tactics to support your rules.

If you get antsy when hitting a challenging part of a task, and distract yourself by “taking a break”, write down the rule:

Whenever I am feeling antsy, I must continue with my current task for 5 minutes before taking a break.

Waiting 5 minutes gives time for the urge to subside.

You can refine this rule and add a timer as a tactic to support it by re-writing it as:

Whenever I am feeling antsy, I will set a timer for 5 minutes and continue with my current task until it rings before taking a break.

This moves the adherence of your rule from your subjective experience of time, which can be fudged, to an external, objective timekeeper.

Conclusion

Identifying distraction triggers is crucial to answering the question “Why do I get distracted so easily?”. Without the self-awareness of why you are getting distracted, it’s hard to brainstorm or evaluate solutions that may help improve your focus and productivity.

Once you know what your triggers are, you can then start developing rules and strategies that help you ignore or manage them more effectively.

While it may take time and patience, the rewards of a focused mind and a productive day are well worth the effort. So, start your distraction log today, and embrace the journey towards better focus on a daily basis.