Common time management advice is to “know your hourly rate”. The idea is that if you know how much an hour of your time is worth, you can make better decisions with your time and money.

Lots of articles have been written on how to figure out your hourly rate. If you earn a salary, a common formula is to divide your salary by 2,000, which assumes you work 40 hours per week for 50 weeks per year, taking a vacation the other 2 weeks.

This is a fine starting point, but there are different hourly rates—your time is worth different amounts depending on who you are and what you are doing.

The Purpose of Knowing Your Hourly Rate

Let’s go over some reasons you might want to know your hourly rate. Some reasons include to:

- Decide when to pay someone else to do something instead of yourself

- Understand how much extra money you can save if you work more

- Work to improve your hourly rate by being more efficient

- Convert the price of items into their time equivalent (that TV costs me 10 extra hours of work)

- Find a another job or client that pays you more

Each of these reasons can have different hourly rates. Knowing what those different rates are, and how to use them, can help you make better decisions about your time and money.

Your Gross Hourly Rate

To start off, let’s calculate your gross hourly rate. If you are a consultant paid based on how long you work, use your hourly billable rate. If you are salaried, take your salary and divide by 2,000 (or how ever many hours you are supposed to work).

For instance, if you make $60,000 per year, your gross hourly rate would be $30/hour.

Now this isn’t your actual hourly rate, but it’s a useful starting point.

Your Net Hourly Rate After Taxes

When trying to decide whether to pay someone to mow your lawn or do it yourself, or to figure out how much you can save if you work more, you need to know your net hourly rate after taxes. This is the amount you earn per hour that actually goes into your pocket, so you can spend or save it.

If you are paid W-2, use this calculator to calculate your take-home pay. Change the Pay Frequency to Weekly and then divide the take-home pay by the number of hours you are supposed to work per week.

For instance, someone making $60,000 a year grosses $1,154 a week. After taxes that comes to around $860 for a single person with one allowance and no other deductions, making their net hourly rate about $21.50/hour.

If you are paid 1099, use this calculator to calculate your take-home pay based on your hourly rate, hours worked and expenses, then divide the net amount by your hours worked.

For instance, someone making $50/hour who works 40 hours per week and has $200 of expenses each week brings home about $1,292 per week or $32.30/hour.

Your net hourly rate is much more useful than your gross hourly rate because it’s the amount of money you’ll actually receive for your work. However, as you can see from the calculators above, it requires many more assumptions. So use this as an approximate rate, rather than an exact rate.

Use your rough net hourly rate to:

- Decide to hire someone for a personal service you could do yourself, when their rate is lower than yours

- Figure out how much you need to work to save a certain amount

- Reframe purchases into the amount of time you need to work to earn enough for that purchase

Just knowing your net hourly rate can be helpful when making these and other decisions, but it’s not the only hourly rate you want to pay attention to.

Your Business Delegation Hourly Rate

If you run your own business or do contract 1099 work, using your net hourly rate to make outsourcing decisions can lead to not outsourcing tasks when you should be. That’s because your net hourly rate doesn’t apply to business tasks.

Anyone you hire becomes a business expense. Thus, you should be using your gross hourly rate to make outsourcing decisions.

For instance, if it takes you 2 hours a week to do bookkeeping for your business and you can hire a bookkeeper at $40/hour, it is cheaper for you to outsource that task when you make $50/hour, even though your net hourly rate is only $32.50/hour. That’s because the $40/hour expense goes against the $50/hour you are earning before taxes are taken out.

Keeping this in mind can help you make better decisions around outsourcing the non-core work for your business, so you can focus on what makes you special.

As with everything, there are caveats. The gross hourly rate we calculated above may not be your actual gross hourly rate, since you need to take into account your non-billable time. And if your ability to earn more by working more hours is fixed or capped, it still may make sense to do a task yourself and save the money.

Adjusting for Overhead Effort

So far we’ve talked about your gross and net hourly rate as if they were simply the amount you earned divided by the time you worked. But there’s an important caveat in that calculation: how much time did you actually spend working?

If you earn a salary, you may be working more than 40 hours per week. If you own your own business, you need to spend time doing things that can’t be billed back to a client, such as sales & marketing, accounting and planning.

For many people, these extra hours can add up significantly.

If you are paid a $60,000 salary, but actually work 60 hours per week, your gross hourly rate drops from $30/hour to $20.83/hour, a 30% drop. If you run your own consulting business, it’s not uncommon to spend 50% of your time or more doing non-billable work, making that $50/hour gross rate actually be closer to $25/hour.

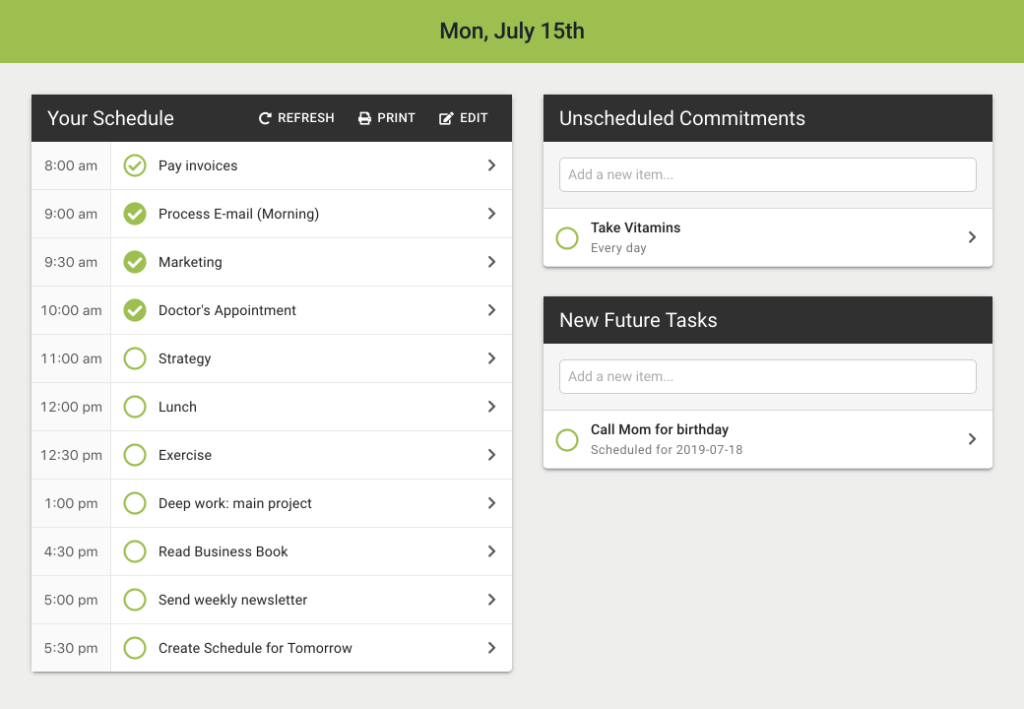

Use a time tracking log to track your actual work hours, and then use that to make adjustments to your gross and net hourly rates.

Adjusting for Startup & Wrap-up Time

Besides ongoing overhead costs, you should also take into account startup and wrap-up time that reduces your hourly rates when making specific decisions.

For instance, assume you’re a contractor making $50/hour working for a client who pays you for 20 hours per week. You like the client, but want to make more money, and don’t have the time to take another client on. You spend a few hours looking around and find 3 contracts each paying $55/hour. Each will last for 3 months. Is it worth it?

Let’s assume you spent 4 hours surfing the web looking for these jobs, 5 hours updating your resume, and then spend another 2 hours per job researching and applying. At this point, you’ve spent 15 hours. Next you’ll need to follow up with each of those jobs. Once one of the jobs gets back to you, you’ll go through the interview process, spend time thinking about the job and then need to wind down your current client. Let’s say all that takes another 15 hours.

So now you’ve spent 30 hours of non-billable time switching to a higher paying contract. But that contract will only last 240 hours (20 hours x 12 weeks). You’ll make $13,200 over that time, but will have spent 270 hours to get that money. Your gross hourly rate after taking into account your startup and wrap-up time is $48.89/hour, less than you were making than if you just stuck with your original contract.

Now this is a highly contrived example, but it demonstrates how unaccounted effort for starting something or wrapping it up can eat into your true hourly rate. And because time spent on starting something new can sometimes be unbounded, especially when the outcome isn’t guaranteed, that time can significantly affect your hourly rates.

The True Cost of Extra Work for a Raise

A similar analysis can be done for people doing extra work to earn a raise. Raises often pay off in the long run, but there is a period where any extra you earn just gets applied to the overhead effort of getting the raise.

If you spend an extra 10 hours a week unpaid for 6 months, and your gross hourly rate is $25/hour, to “break-even” you need the raise to earn you $6,500 ($25/hour x 10 hours x 26 weeks). If you get a 10% raise to $27.50/hour, it will take you 2,600 hours ($6,500 / $2.50), or about 1 year and 3 months working 40 hours per week before you are compensated for the extra time you spent.

Working for a promotion is rarely purely a financial decision, and can be worth it in its own right. But it can be helpful to understand when you are putting in too much effort for too little reward.

The True Cost of Purchases

Similarly, if you are deciding to make a purchase, the cost of that purchase is not just the cost of the item itself, but the cost of all the time that went into that purchase. So if your net hourly rate is $20/hour and it takes you 5 hours of research to decide to buy a $100 piece of software, it actually cost you $200.

That’s not to say you shouldn’t spend the time, since there’s a cost to making the wrong decision. But at some point, especially when researching purchases, you’re adding to the total cost without much added benefit.

Fixed, Elastic & Capped Income

Whether your income is fixed, elastic or capped changes how you should calculate your hourly rate for different purposes.

A fixed income is one where you are paid the same amount no matter how much extra you work. An elastic income is one where you have the option to earn more by working more, and a capped income is an elastic income that has a limit to how much you can earn.

Say you are thinking about whether to hire someone for $20/hour to mow your lawn for 3 hours versus mow the lawn yourself. If you are paid $30/hour with the option to work more hours, you can easily trade your time for their time and come out ahead—just work an extra 2 hours and you’ve saved yourself an hour.

But if your income is fixed or capped, the decision may not be so easy.

With a fixed income, any money you spend reduces the total amount you can save or spend elsewhere. In this case, it’s better to ask yourself what else you could use that money for, and not make the decision based on your hourly rate.

Instead of having an hourly rate, use a trade-off rate: a non-monetary rate of something you’re willing to give up in exchange for something else.

For instance, say it costs you $60 to go out to a nice dinner with your spouse. Paying someone to mow your lawn is now equivalent to 1 nice dinner. If you’re willing to skip a dinner, hire the person to mow your lawn; otherwise do it yourself.

Rather than analyzing potential expenses based on your hourly rate, analyze them based on what you’re willing to give up for the expense.

If you have a capped income, or an income that’s a combination of fixed and elastic, such as a salaried job with a contract work side hustle, then you can use a combination of these strategies. Give yourself a set number of hours that you can use for elastic expenses, and then once you run out of these hours, use your trade-off rate for any further expenses.

Next Steps

Calculating your hourly rates can be helpful in making all sorts of decisions. But the rate you use depends on the specific decision and your own personal situation. Use the resources listed in this article to calculate:

- Your gross hourly rate to use for business expenses, or to compare your compensation to the market

- Your overhead-adjusted net hourly rate to use for personal expenses and savings

- Your startup-adjusted net hourly rate to use for specific projects, like looking for new client or making a small purchase

Finally, be aware that how you use your hourly rate depends on how you earn your income. Advice directed at someone with highly elastic income, who can simply work more hours to make up for money spent, doesn’t often apply to those with a fixed income, with little opportunity for advancement.